The Road We Came

Description

Scroll down for commentary on each video by historian Eric K. Washington.

The Road We Came is a new opera- and song-based project that explores the composers, musicians and places that define the rich Black history of New York City through a series of self-guided, musical walking tours.

Celebrating a collection of never-recorded and seemingly lost classical compositions by Black composers, The Road We Came uses filmed musical performances and spoken narration to connect audiences to the musical timeline of Harlem, Midtown/Hell’s Kitchen and lower Manhattan. From the home and texts of the prolific poet Langston Hughes, to Lincoln Center, to the African Burial Ground National Monument, and beyond, The Road We Came opens windows to the past and re-frames the present. The Road We Came is a multi-media collaboration between On Site Opera, Ryan & Tonya McKinny’s Keep the Music Going Productions, award-winning biographer and Harlem historian Eric K. Washington, and critically acclaimed baritone, Kenneth Overton, who was the featured soloist of the tours.

AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND,

TESTAMENT TO EARLY

BLACK GOTHAM

The African Burial Ground National Monument, at the southwest corner of Duane Street and Elk Street, memorializes the burial place of approximately 15,000 Africans,, both enslaved and free, during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today it is a mere fraction of a sprawling seven-acre plot that was active from the 1690s until 1794, but it highlights what was once the country’s largest colonial-era cemetery for enslaved African people.

The area encompassed the site of today’s nearby City Hall Park, whose popular uses were both frenzied and wretched. It was the general rendezvous of Pinkster, an Africanized adaptation of the Dutch Christian Pentecost that was one of the most anticipated holidays in 17th- and 18th-century New York. The annual Pinkster Frolic, as it was called, was celebrated in the Hudson Valley region from this city up to Albany. Perhaps comparable to New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, the total abandon of the days-long festivities transcended its cultural association with local enslaved and free Blacks — it enthralled the broader population as well. Not everybody was amused. In 1811 the Albany State Legislature passed the “Pinkster Law” — which coincided with the rise of today’s City Hall mansion — prohibiting any person “to march or parade, with or without any kind of music” on any public streets. But surely many elders recalled the park’s more somber uses only seventy years before — as when in 1741, thirteen enslaved black men were burned at the stake in the shadow of this burial ground.

During its active period, this burying site sometimes drew controversy. In 1788, shortly after the American Revolution, some Black New York citizens petitioned the Common Council to stop frequent invasions of their burial ground by grave robbers. The culprits were so-called “resurrection men,” young medical students from New York Hospital in search of bodies from fresh burials to dissect. Despite the Black citizens’ formal protest against the “sallies of exces,” by the students — who rowdily plundered the graveyards of the city’s most disenfranchised — the city turned a deaf ear to their petition.

.

Now, the National Park Service stewards the site as the African Burial Ground National Monument, which exhibits extensive information on the history, anthropology and archaeology of the site, using research conducted by Howard University. The monument itself comprises several visible components — The Wall of Remembrance is the looming, highly polished granite elevation facing Duane Street, whose text inscriptions offer a timeline of major historical events leading up to the creation of the African Burial Ground. Its opposite, south-facing side is the Memorial Wall, whose engraved map puts in perspective the burial ground’s original size and location — it once stretched well beyond the present memorial site. On the west side of the plot, the grassy mounds entomb the Seven sarcophagi, which house the 419 African ancestral remains of those who were exhumed during building construction, and then ceremonially re-interred. Four of the granite pillars serve as symbolic guardians to the Ancestral Libation Chamber. The Circle of the Diaspora is the perimeter wall encompassing the Ancestral Libation Court.

The rediscovery of this forgotten burial site in 1991 ignited a groundswell of active interest and research in local Black history nationwide.

36 LISPENARD STREET,

FORMER SITE OF THE HOME OF

DAVID RUGGLES, ABOLITIONIST WRITER

In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, an African American man named David Ruggles (1810-1849) was a prominent resident here on Lispenard Street. Ruggles was an early practitioner of hydropathy, or “water cure” — the treatment of certain pains and illnesses with the use of water — that is recognized today as hydrotherapy. But most New Yorkers knew him better as a writer of antislavery tracts. In about 1838 he began to publish The Mirror of Liberty, said to be the first magazine that was owned and edited by an African American, and for several years he issued numerous pamphlets and broadsides from his own pen and printing press on this block. Oddly, Ruggles is largely unsung today, for he was not only one of the most prominent “conductors” of the storied Underground Railroad, but he stewarded one of its most exalted passengers.

Ruggles was also a founder of the New York Committee of Vigilance, a biracial abolitionist organization that tirelessly confronted and thwarted so-called “blackbirders,” or slave catchers, who set out to track down and recapture Black runaways from the South in New York. Being bounty hunters, bands of men also frequently kidnapped free Blacks — as in the case of Solomon Northup, whose 1853 memoir inspired the award-winning movie, Twelve Years a Slave — for whom they could just as well make illegal sales to southern slavers.

For the abolitionists’ part, Ruggles and the Vigilance Committee strove to be timely enough to thwart the nefarious work of slave catchers. They took great risks to rescue a fugitive, to whom they offered shelter and legal assistance. Ruggles himself greeted one of those fortunates. On September 3, 1838, a young man undertook his daring escape north. Traveling by train and boat from Baltimore, through Delaware, to Philadelphia, he found safe harbor in New York under Ruggles’s roof at this site. Destined for greatness, that particular young man became the legendary orator, writer and statesman Frederick Douglass.

COOPER UNION AND WANAMAKER’S,

TOUCHSTONES OF BLACK POLITICS

AND MUSICAL ARTS

The looming brownstone building at the north end of today’s NoHo Historic District opened as the Cooper Institute in 1859. Of the countless public addresses and meetings in its Great Hall auditorium, perhaps the most often cited was one that took place on February 27, 1860. Here is where some 1,500 New Yorkers heard Abraham Lincoln deliver his famous “Cooper Union Address,” whose salient issue was the question of slavery’s further expansion into the western territories. The speech is credited with cinching Lincoln’s position as that year’s Republican Party candidate for the Presidency. Many decades later, the late President Abraham Lincoln would have a somewhat different relevance to a building just across the street: the former Wanamaker’s Department Store on East 8th Street between Broadway and Lafayette Street.

In 1909 Philadelphia department store magnate John Wanamaker, an ardent music lover, began publishing The Opera News magazine. And five years later his musical passion took center stage here at his lavish New York City store. For a weeklong Lincoln’s Birthday commemoration in February 1914, Wanamaker’s in-house concert impresario Alexander Russell engaged the renowned African American soprano and educator Daisy Tapley to train some two dozen singers from the store’s numerous Black employees into a fine chorus. Tapley accompanied them on piano, and also led a separate 30-piece orchestra of musicians assembled from the store’s Black workforce.

In the pages of his Opera News, Wanamaker inaugurated the store’s new Lincoln Emancipation Jubilee Club, and explicitly championed his employees’ deep-rooted repertoire as “probably the nearest approach we have to ‘folk music’ in the United States.” Indeed, appearances of the Wanamaker Colored Chorus, as the musical workers were best known, drew shoppers and visitors to the store’s rotunda or auditorium as a years-long tradition — whether for Lincoln’s Birthday, the store’s Easter Operatic Festival or other seasonal occasions—and also exposed their talents to outside engagers. Their performances often included such esteemed musical guests as composers Will Marion Cook, R. Nathaniel Dett, Harry Burleigh and J. Rosamond Johnson.

The latter reminds us that Wanamaker’s, despite a famously Black-friendly hiring and musical-promoting practice, was not immune to prevailing racial prejudices. One day during WWI, while shopping at Wanamaker’s for the soldiers canteen in Harlem, Mrs. J. Rosamond Johnson and singer Blanche Dean Harris were refused service in the store’s cafeteria. The distasteful incident may well have inspired one of John Wanamaker’s published advertising mottos: “A man that blackens another man's character does not whiten his own."

FORMER COLORED SCHOOL No. 4,

RECONSTRUCTION-ERA

RACIAL CASTE SCHOOLHOUSE

This unassuming three-story brick building at 128 West 17th Street in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood recalls New York City’s official racial-caste education system throughout most of the nineteenth century. Built about 1853, the structure is a rare extant example of an 1844 architectural model for public grade school buildings throughout Manhattan. For thirty-four years, from 1860 to 1894, it was known successively as Colored School No. 7, Colored School No. 4 and Grammar School No. 81 — although most notable by its Reconstruction-Era moniker Colored School No. 4.

The school’s driving spirit was Sarah J.S. Tompkins (1831-1911), who on April 30, 1863, during the Civil War, became one of the city’s most prominent Black public school principals. In March 1871 she initiated a series of public lectures in her new schoolhouse with the renowned former abolitionist, orator and statesman Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. Tompkins eventually married him nine years later, becoming thereafter familiar as Sarah Garnet.

By the late 1870s the Board of Education was persuading the state legislature to absorb segregated schools into the general system. However, while the city’s Jim Crow education system was admittedly a relic of the slavery era, Black educators had honed their "colored" schools into crucial pillars of African American communities. Their proposed abolition inevitably galvanized Sarah Garnet and many others to protest.

On February 12, 1883, a mass meeting of Black citizens — encouraged by a letter from Frederick Douglass — implored the Board of Education either to retain Black teachers as equals with white teachers, or else to preserve the “colored” schools. A year later, New York’s Governor Grover Cleveland signed legislation saving two of the separate schools. One of them was Garnet’s Colored School No. 4, hence renamed Grammar School No. 81, while remaining de facto African American until its disuse in 1894.

During her tenure, Principal Garnet was ever the activist. Perhaps inspired by her sister Susan McKinney Steward, the state’s first Black woman to earn a medical degree, in 1895 Garnet co-founded an association to build a community hospital. Garnet later founded the Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn, which in 1908 joined with the National Association of Colored Women to petition the U.S. Congress for women’s right to vote. Upon her death in 1911, civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois spoke at her memorial, and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett sent a testimonial letter.

Another of the school’s remarkable teachers was J. Imogen Howard. In 1893 Howard represented New York State at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the only Black manager at the World’s Fair. Similarly, in 1900 she was the only Black educator of five whom the Evening Telegram treated to the Paris Exposition as winners of its great teachers competition. The school’s other teachers included Susan Elizabeth Frazier, who was New York City’s first Black teacher assigned to a mixed public school; and William Appo, one of the most influential African American music educators in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Notable graduates included violinist and preeminent orchestra leader Walter F. Craig, who was the first black member of the all-white Musical Mutual Protective Union; freemasonry historian Harry A. Williamson; and James H. Williams, Chief “Red Cap” Attendant at Grand Central Terminal, whose organization of Black college men comprised an essential work force at the august railroad station for nearly half a century.

LINCOLN CENTER,

FROM MUSIC HALL TO GRAND OPERA

Although today’s Lincoln Center is an indisputable cultural magnet, a humbler, yet galvanizing happening for African American performers foreshadowed this grand plaza. The ballad you just heard was born here in 1921, when the smash hit musical, Shuffle Along, opened at the 63rd Street Music Hall, at 22 West 63rd Street. The show, with music and lyrics by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, immediately made theater history, being the first all-Black production on Broadway. It introduced the songs “Love Will Find A Way” and the lively “I'm Just Wild About Harry” as popular standards of the American Song Book. Indeed, the show also established the theater’s claim as a “legit” Broadway house for the next twenty years. No sooner had its opening night curtain risen, than the show began making stars, and later legends, of many of its Black creators, cast and even members of the orchestra.

One of Shuffle Along’s pit musicians was a 25-year-old Black oboist named William Grant Still. Later known as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers,” his eminent career produced roughly 200 works, including symphonies, ballets, chamber music art songs, and operas. In fact, Still’s three-act Troubled Island, produced in 1949, was the first opera by a Black composer to be performed by a major company, the New York City Opera. Major, yet not quite the Met.

Since it was founded in 1883, the Metropolitan Opera, then located on Broadway and 39th Street, has surely deferred the dreams of as many Black musical artists as it has uplifted. Even a Met insider like Italian tenor Edoardo Ferrari-Fontana — who in 1925 awarded scholarships to two Black sopranos in Harlem with hopes of priming them for Aida — found his goal to be a pipe dream. When the Met presented Ernst Krenek’s German jazz opera Jonny Spielt Auf in 1928, it opted to cork up a white baritone for the hero’s role of a Black band leader rather than risk offending parterre subscribers; a tack repeated in 1933 for Louis Gruenberg’s The Emperor Jones, although it signed a Black dance troupe for authentic local color.

Not until 1948 did the sixty-five-year-old opera company sign a Black singer, soprano Helen Phillips, but as a chorus member of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana. Then in 1955 the Met finally gave the world renowned contralto Marian Anderson her long overdue opera debut in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera.

In 1966 the venerable opera company quit the Old Met. In an artistic first, Black soprano Leontyne Price debuted the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera House here at Lincoln Center, singing the title role of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra. However, the opera company’s 136-year longevity has still sidestepped a single work by a Black composer in its repertoire, until now. On opening night of the 2021–2022 Metropolitan Opera season, Grammy–winning jazz composer Terence Blanchard made history when the curtain rang on his opera adaptation of Charles M. Blow’s memoir, Fire Shut Up In My Bones.

CARNEGIE HALL,

PIVOTAL SHOWCASE OF

BLACK MUSIC AND TALENT

On June 15, 1892, a year after Carnegie Hall opened at 881 Seventh Avenue, Madam M. Sissieretta Jones — her bosom opulent with ribbon medals conferred from dignitaries around the world — became the first African American singer to take the august stage. Jones had been dubbed “The Black Patti,” in comparison to popular Italian soprano Adelina Patti, and her successful recital naturally made Carnegie Hall an aspired pinnacle of achievement to a host of Black artists. Count among them musical lion James Reese Europe, who in 1912 performed a Concert of Negro Music with his renowned Clef Club Orchestra to benefit the Music School Settlement for Colored People, then in San Juan Hill.

Carnegie Hall’s cachet certainly sparked keen interest in a certain concert that the New York Branch of the NAACP announced in early 1917. The Negro Folk Song Festival: A Chorus of Three Hundred Voices, under the direction of esteemed Black soprano and music educator E. Azalia Hackley, was also to feature H.T. Burleigh, J. Rosamond Johnson and Will Marion Cook. The concert underscored a period of rapt attention by mainstream audiences in African American “folk songs” — variously called Sorrow Songs, Negro Spirituals, plantation melodies or Southern dialect songs.

“The Negro folk song stands today,” wrote NAACP cofounder W.E.B. Du Bois in the Festival’s program, “as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas.” Noted white music critic Henry Edward Krehbiel agreed. “Folk songs are born, not made,” he wrote, adding that “their charm has been widely recognized.” Unfortunately, when Mme. Hackley was afflicted by a sudden ear infection, the highly anticipated concert had to be cancelled. Yet its significance prevailed. Mme Hackley recovered, and she took the Negro Folk Song Festival to Baltimore, New Orleans and elsewhere, inspiring similar African American musical surveys for years to come. Notable variations on this theme included A Night of Negro Music in 1928, in which composer W.C. Handy, the putative “Father of the Blues,” highlighted several new arrangements of spirituals and work songs; and Two Wings: The Music of Black America in Migration in 2019, in which jazz pianist Jason Moran and mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall-Moran employed personal family lore for their musical journey.

For over a century, Carnegie Hall has showcased the confluence of African American musical tradition and European art song for the world’s appreciation. It has launched the meteoric rise of generations of Black classical music luminaries whom America’s most hallowed and historic musical societies excluded on the grounds of race alone — notable among them tenor Roland Hayes; and contralto Marian Anderson, who became an original board member of the new Carnegie Hall Corporation in 1960 until her death in 1993. And the Hall debuted the fully integrated Symphony of the New World — which included women, unlike the New York Philharmonic — during the height of the Civil Rights era. To be sure, Carnegie Hall’s stage has elevated countless Black musical artists, like Sissieretta Jones before them, to a clearer musing on what stellar possibilities might be in the offing.

FIFTH AVENUE AND

THE SILENT PROTEST PARADE OF 1917

New York City’s Fifth Avenue has long represented old wealth, posh shopping and genteel insouciance. But on one midsummer day in 1917 this iconic street was the scene of an African American civil rights march. The likes of it had never been seen. Nor heard. The event took place in utter silence.

The Negro Silent Protest Parade of July 28, 1917, was sparked by a vicious incident almost a thousand miles away from New York. Anti-Black labor resentments in East St. Louis, Illinois, had set off a rampage of thousands of the white townspeople, who attacked Black residents indiscriminately, and executed about two hundred in broad daylight, several by lynching. The aftermath of torched neighborhoods rendered some 6,000 Black residents homeless.

The massacre pitched the country into expressions of national disgrace and remorse. Here in New York, the incident effectively mobilized over 10,000 Black men, women and children to march wordlessly down Fifth Avenue, one of the city’s most responsive arteries. Except for bold-lettered banners, and the steady somber beat of a drum, the human column was silent.

The momentous event catalyzed James Weldon Johnson, then a field secretary for the NAACP, to mobilize numerous Black college students. It also engaged some of Grand Central Terminal’s Red Cap porters, accustomed to fielding tourist questions, to perform as sort of an ad hoc information source about the march.

Despite its name and method, the Silent Protest Parade of 1917 was operatic in its impact. The demonstration forged a movement which changed the organizational infrastructure of the NAACP, and which set the stage for future massive American Civil Rights protests for generations to come.

PROGRESSIVE-ERA

MUSIC SCHOOL AND CIVIC CENTER FOR

AFRICAN AMERICAN TALENT

On October 8, 1914, the Music School Settlement for Colored People opened in the adjoining townhouses, 4 and 6 West 131st Street. It was founded in 1911 in San Juan Hill (today’s Lincoln Center area) by a group of social benefactors of the settlement house movement; their aim, to offer high-level music education to Black children whom other institutions often barred by race or prohibitive fees. Leading the initiative was David Mannes of the New York Symphony Orchestra, driven by personal gratitude to the Black violinist who first instructed him as a boy; along with his wife, pianist Clara Mannes, the sister of Walter Damrosch, director of the Institute of Musical Art. African American musicians David I. Martin (violinist) and Helen Elsie Smith (pianist) were the first musical supervisors.

For this Harlem school, Mannes appointed black composer J. Rosamond Johnson as supervisor. Johnson was renowned for collaborations on Broadway with his brother James Weldon Johnson, and especially for their transcendent, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” a song exalted since 1900 as the Black National Anthem. Rosamond equipped the school with four pianos and $1,500 worth of instruments (about $40,000 today). His impressive teaching staff included Mme. Selika Williams, the soprano dubbed “Queen of Staccato,” and the first Black singer to perform at the White House (for President Rutherford B. Hayes); and H. Lawrence Freeman, the grand opera composer dubbed “the Black Wagner,” whose Negro Choral Society featured annually at Madison Square Park’s Tree of Light holiday festival years before Rockefeller Center’s. Equally impressive were the school’s neighbors — legendary James Reese Europe, who conducted several Carnegie Hall benefits for the school, lived down the block, and right across the street was the townhouse of a long esteemed concert patron, realtor Philip A. Payton, called the “Father of Black Harlem.” The first enrollees included a seven-year-old violin student who grew up to be stage and screen star Canada Lee.

A musical keynote of the school’s grand opening, played by the Coleridge-Taylor Quartet, was a song that revealed the Johnson brothers’ wide influence as collaborators: “Since You Went Away.” Metropolitan Opera baritone Pasquale Amato was infatuated with this “Southern-dialect” song, and his performance of it the year before induced other international stars to broaden their own classical repertoires with African American music. When Rosamond sang the song himself at the funeral of venerable millionaire businesswoman and board member Madam C.J. Walker in 1919, the death of the Johnson brothers’ mother that same year gave it added poignancy.

The Settlement School closed in 1919, and the first directors’ Martin-Smith Music School a few blocks away in Harlem assumed its activities. But while short-lived, the Settlement School remained a touchstone in the growing firmament of formal musical training centers and societies for African Americans, and for their increased admission to schools once closed to them.

As for the song, the popularity of “Since You Went Away” continued to grow. Upon James’s death in 1938, as he lay beneath a wreath from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the renowned Southernaires radio quartet sang the author’s unforgettable words. And decades following Rosamond’s own death in 1954, new generations of Black composers have been inspired to set to music his brother James’s original 1899 poem, Sence You Went Away, including H. Leslie Adams (1976) and Lori Celeste Hicks (2014).

LANGSTON HUGHES HOUSE,

LONGEST AND LAST RESIDENCE OF

NOTED POET, AUTHOR AND ACTIVIST

Although Langston Hughes’s ashes reside at the Schomburg Center, his most noted address in life was the Langston Hughes House here at 20 East 127th Street. This modest Harlem row house was built in 1869, shortly after the Civil War, yet almost a century passed before it truly seemed to come to life. In 1947 Emerson and Ethel (Toy) Harper, Langston’s longtime adopted uncle and aunt since the early 1930s, invited him to move in with them. And for the next twenty years, from 1947 until his death in 1967, the renowned poet, author and activist made his home on the house’s top floor.

By the time he moved here in 1947, Langston was already distinguished as one of the foremost literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance era. The comfort of this address appeared to fuel his prolific writings. He continued to publish poetry. He also created a humorous book series — introducing the character of Jess B. Semple (Just Be Simple) — that exalted the common man of Harlem. And in other books he explored such Black cultural and historical topics as jazz, folklore, the West Indies and Africa.

While living here Langston made numerous musical collaborations as an opera and musical theatre librettist, notably for a show that opened on Broadway the same year he moved in. Langston’s lyrics for the operatic musical, Street Scene — based on Elmer Rice’s 1929 Pulitzer Prize-winning play — captured the vibrancy of a New York tenement streetscape that infused composer Kurt Weill’s Tony Award-winning score. He also wrote songs composed by his hosts Emerson and Toy Harper, both active theater musicians, that were published and performed,

Langston lived here for the longest stretch than he’d lived anywhere else. The “Langston Hughes House” is an officially designated landmark of both the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the National Register of Historic Places. The house evokes a palpable connection to the venerable “Langston.” But it also duly invites us to meet a host of other fascinating people like the Harpers, (to whom Langston dedicated his 1940 memoir, The Big Sea), and notable collaborators like composer Margaret Bonds — who populated the Harlem that so inspired his literary career.

NAMA

AMERICA’S OLDEST CONTINUING

ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL MUSICIANS

The New Amsterdam Musical Association (NAMA) at 107 West 130th Street in the Central Harlem Historic District, was organized in 1904, and incorporated on January 19, 1905. It is the oldest continuing African American musical association in the United States. As was typical of the time, NAMA formed in part because whites-only guilds routinely barred membership to Black musicians.

The organization’s driving force was William A. Riker, who in 1900 had founded Riker’s Black Concert Band and Orchestra, which four years later he converted into NAMA. The association began in the West 50s, then in 1906 followed the Black community’s shift to Harlem, where it eventually bought this brownstone townhouse in 1922.

Striving to promote “the interests of Afro-American musical talent,” Riker worked diligently to secure binding, contracted work agreements and professional equity for Black musicians in both engagements and repertoire. His own musician’s sensibility predisposed him to showcase NAMA’s talented musicianship as a top-tier society orchestra as well as a uniformed military band, the latter being a common feature for outdoor events. NAMA’s first manager was Riker, who filled the role for many years, and its first president was Afro-Cuban-American composer Pastor Penalver.

After incorporating in 1905, the association’s earliest engagements fairly represent its immediate success. That first year alone, NAMA’s military marching band accompanied Brooklyn’s Henry Highland Garnet Republican Club for Theodore Roosevelt’s second presidential inauguration in Washington, D.C.; and its orchestra played for the annual National Negro Business League conference, at the famous Palm Garden on East 58th Street and Lexington Avenue, presided over by Booker T. Washington.

Rooted in Riker’s Band, NAMA has been regarded as the basis of the legendary Clef Club, founded in 1910 by James Reese Europe, and of all Gotham’s subsequent Black musical aggregations. The organization comprised Black musicians performing in all genres, including classical composers like William Grant Still, though jazz practitioners came to dominate its still active membership.

STRIVERS ROW

CHIEF WILLIAMS HOUSE,

RAILROAD LABOR FIGURE WHO

HIRED HUNDREDS OF BLACK COLLEGIANS

James H. Williams lived at 226 West 138th Street, one of the two tree-lined and celebrity-lined blocks known jointly as Strivers Row. About 1919 this exclusive whites-only enclave — comprising 138th Street and 139th Street, between Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue) and Frederick Douglass Boulevard (Eighth Avenue) — finally opened to African Americans. Williams, who bought his house in 1919, was part of an unusual mix of well heeled medical professionals, civic leaders and arts figures. His famous neighbors included surgeon Louis T. Wright; “Father of the Blues” composer W.C. Handy; bandleader Fletcher Henderson; architect Vertner Tandy; and grand opera composer H. Lawrence Freeman. By comparison, Williams’s trade was deceptively staid — he headed the army of once ubiquitous Red Cap Porters at Grand Central Terminal. But it was not lackluster.

“Chief” Williams, as he was known, was famously associated with two of New York City’s pioneering Black civil servants: his Assistant-Chief Red Cap and friend, Samuel “Jesse” Battle (living across the street), who became the city’s first Black policeman in 1911; and Wesley Williams, his son, who became Manhattan’s first Black fireman in 1919. But for decades the Chief’s own prominence came from hiring legions of young Black students, from throughout the Eastern Seaboard, who came looking for work to pay college costs. “Only because the Chief had a big heart and was proud of his race were hundreds of young colored men able to go through college,” said Harvard (and Grand Central) alum Earl Brown, who as City Councilman in 1950 initiated the bill creating today’s Frederick Douglass Circle above Central Park. For Chief Williams it was a point of pride that an estimated forty percent of his Red Cap corps was college educated, exceeding other Terminal departments.

Emulated in railroad stations nationwide, Grand Central Terminal’s racialized and often exploitative Red Cap system required men to be “walking encyclopedias” of the city as they lugged all manner of travelers’ belongings through the station. But being barred by race from most other job options, multitudes of Harlem-based Black men coveted the Jim Crow work. Under Chief Williams, they proactively formed various civic, social and athletic societies which effectively transformed an inauspicious job into a platform of advantage.

Some familiar figures who emerged from ”red-capping” into more worldly-wise pillars of Harlem’s Black middle class include concert singer and humanitarian activist Paul Robeson; minister and U.S. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr; National Urban League civic leader Lester Granger; and Broadway actor and restaurateur Richard Huey.

One particular Red Cap that Chief Williams hired, a student of the Institute of Musical Art (the forerunner of Juilliard), was literally a work in progress: John Wesley Work III descended from one of the most influential names in African American music. His namesake grandfather led the Fisk Jubilee Singers during that group’s first international tour in 1871; and his father, Work Jr. (or II), led the Fisk Jubilee Quartet. Not surprisingly, Work became an illustrious composer and ethnomusicologist, and the father of singer John Wesley Work IV.

Others you might like

After Glow

NBC’s The Voice finalist John Holiday and poet Marc Bamuthi Joseph lead us through a sensual, modern retelling of Schumann’s iconic song cycle Dichterliebe.

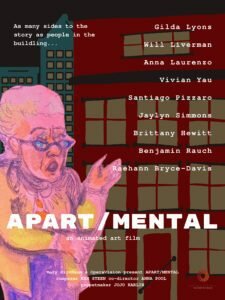

APART/MENTAL

Two Jewish women in New York, one says, "Do you see what's going on in Poland?" The other says "I live in the back, I don't see anything."

-Henny Youngman

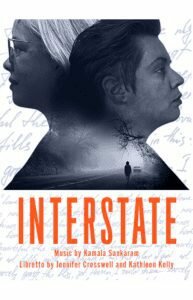

Interstate

The road from trauma to tragedy. Interstate is the story of Olivia and Diane, who shared a childhood in vulnerable, unsafe circumstances before life sent them down different roads. The adult Diane reaches out from her stable life to Olivia, a prostitute in prison for murder. Interstate blends the horror and violence of Olivia’s life with the tenderness of old friendship and the hard questions of accountability.

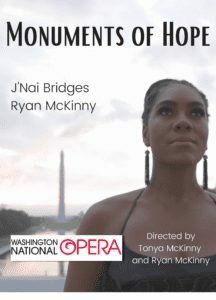

Monuments of Hope

Mezzo J’Nai Bridges and bass-baritone Ryan McKinny perform in front of D.C.’s most iconic monuments—representing our collective memories and shared hope for a more perfect future.

Obscura Nox

In this modern retelling of Plato's Allegory of the Cave, a woman is cloistered in a prison of her own making until a mysterious stranger shows her a way out.

On Lost Time

A new Harper Henly film set against the iconic and historic backdrop of the Chicago Cultural Center.

Featuring

Joffrey Ballet company dancers Brooke Linford and Graham Maverick.

Subversive

Subversive is an experimental dance film and afro-futurist electronic soundscape by Marcus Amaker, poet laureate of Charleston and Academy of American poets fellow.